At some point in time some have Peter as belonging to the 46th Regiment of Foot. Usually such records are published, and provide the names of the Officer whose commission is being purchased.

That does not seem to be the case with this information.

But the 46th Regiment of Foot, a British unit, was not in Ireland, and it arrived in Australia in 1814.

South Devonshire The 46th Regiment arrived in Australia to replace the 73rd Regiment 1st Battalion Highland in February 1814,which was then relieved by the 48th Foot The Northamptonshire Regiment in 1817.

On the 11th of June 1813 the regiment sailed on board the transport "Preston" for Portsmouth. Following its arrival at Spithead, the Regiment received orders to proceed to Cowes in the Isle of Wight. The regiment embarked on the 23rd of August 1813 on board the transports "Wyndham", "Three Bees" and "General Hewitt" , and arrived at New South Wales in February 1814.

Following the Regiments Service in New South Wales and on the 8th of September 1817 the Regiment embarked in three divisions at Sydney Cove on board the "Matilda", "Lloyd" and "Dick" and arrived at Madras on the 16th of December 1817

Benjamin Lett, Esq. Templeshelin, died, 1855.

Mr. William Lett, Tomsallagh, Enniscorthj,died,1871.

The Rev. William Thomas Lett, rector of Derryvullen, died, 1857. He was a native of the County Wexford.

Stephen Lett, Esq., merchant, Enniscorthy, died, 1866.

1850, mention is made regarding Mrs Elizabeth Garde, the owner of the lands which Joshua Sutton, and Charles Lett now aged 71, being the only survivors of the plantation measure, and said premises are in possession of Ralph Lett Esq and undertenants.

Throughout his life Peter Lett mentioned he was a Mariner, not Militia.

In fact, Peter was a Mariner. He worked on the ships of the East India Company.

From its first charter in 1600, the English East India Company operated one of the world's most extensive commercial shipping operations in support of its trading enterprises during the colonial period.

The Maritime Service was the company's merchant or mercantile fleet. It was responsible for carrying cargoes outward to the east, returning richly laden with exotic goods which found a ready, and profitable market in Europe.

The East India Company had obtained a monopoly of trade to the east. This was strictly enforced, and no other ships could trade in territory where it had established its bases. The rules were relaxed a little in 1813, and other ships were licensed to trade in some areas, but not in all. For example, it was still only Company ships that were allowed to trade in China.

In 1834 the Company's entire monopoly came to an end, and the Maritime Service was disbanded, although the Company continued to administer its territories in Asia for many years, and ships belonging to many nations were then trading to and from the east.

This website aims to provide some basic information on the many ships and voyages of the East India Company's Maritime Service.

In all likelihood, Peter joined such a ship in Ireland, and enjoyed many exciting voyages around the world, until 1804.

During this time in history, the French were very active in the shipping routes.

Bell's Weekly Messenger of 15th July 1804 reported:

The Countess of Sutherland, also captured by Linios, was a country ship which had brought cargo to England on a private account, and was returning with considerable property belonging to private Merchants. She is supposed to be the largest private ship ever built in India, being of 2000 tons burthen.

The Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal of 28th August 1804 reported:

"The daily reports of the French squad made many captures of our ships in the Indian and Chinese seas, we must in a certain degree, condemn, when there can be no authority for such rumours; as the last news of the enemy's operations are down to the month of May, which only confirms the former accounts, the the ships Countess of Sutherland and the Admiral Aplin, with the Bencoolen brig, had been taken and carried into the Mauritius.

The London Courier and Evening Gazette of 31st December 1804:

Madras June 13 - We some time since, have to state the capture of the ship Henrietta, Captain Somerville, by one of Admiral Linois' squad to the Eastward: she was carried by the captors to Batavia, where disease and death soon reduced the number of the Frenchmen in charge of her, to a small and feeble hand:- the Syrang and Lascars, who were kept on board, and obliged to work in the delivery of her cargo, observing the diminished numbers of the enemy, formed a plan for the recovery of the vessel - this they effected with much spirit, throwing a few of the Frenchmen overboard, making prisoners of the rest, and conducting the Henrietta to Penang, where she has since arrived in safety.

Morning Chronicle of 3rd January 1805

Calcutta July 4 - Yesterday arrived the Danish ship the Elizabeth, Captain Hack, from Batavia, last from Bencoolen, on the 28th May.

The following persons, prisoners of war, are passengers on board her, from Batavia:- Captains W.Somerville and Charles Egglestone, late commanders of the ships Henrietta and Countess of Sutherland; Mrssrs. Alexander Robertson, John Watson, Peter Lette, John Stevenson, T.E.E. Sherburne, Peter Lawson, William Daniel, Robert Freeman, William Sutherland, Nicholas Meeton, officers of ships; with twenty natives all prisoners of war.

By private letters from Bencoolen, received by the above conveyance, we are happy to find, that the expedition that had been fitting ut at that settlement, had sailed for Mouchie, and dropped anchor before that fort, on the 14th April last.

We shall continue to pay every attention to such parts of the Parliamentary Debates as are connected with the Naval History of the present period : but perhaps from the press of other articles this will be repeated at intervals: only being careful that it may tend to form a complete historic narrative when the Volume ii followed.

Private letters from Bencoolen, we find, that the Expedition which had been fitted out at that Settlement, had sailed for Mouchie, and dropped anchor before that Fort on the 14th April last.

Our demand against the Rajah of the place not having been acceded to, the Ships were moored within pistol shot of the walls of the Fort, and, after battering for some time, the place was stormed with the loss of about 50 killed and wounded on our part.

The Ships suffered a little in their masts and rigging ; 83 pieces of cannon were found in the Fort.

The terms granted to the enemy were the same offered to them previous to the storm, viz. to make good the value of the Ship Crescent, plundered at Muchie some time since, and to reimburse us the expense of the Expedition fitted out against them : these terms were finally agreed to, and six Chiefs delivered up as hostages for their due performance.

1804. Admiral Linois' Squadron. On the 6th instant a small cutter arrived at Fort St. George from Bencoolen, which she left the beginning of January ; and brought the distressing account of the arrival of the French squadron under the command of admiral Linois j

The above reports confirm that he was a Mariner.

Thanks to research from Carol Brill, all this information is prior to her report post 1808.

Reports suggest that Peter Lett married Elizabeth Peck in Sydney, and the marriage certificate cannot be found.

Well, he did marry Elizabeth, but not in Sydney, but in India.

How would Elizabeth arrive in India?

Elizabeth and her sisters, were not mentioned on the shipping records of the Porpoise, as returning from Norfolk Island in 1808. Given that the information on the plaques in St David's Park Hobart are incorrect in many of the other ships, then that would explain why.

Elizabeth's sister, Jane Peck went to England as a servant of Col Sorrell, in 1824. The rather large family were no doubt, in need of support, and removing their daughters might have assisted their financial requirements.

As a member of the East India Company, Peter, no doubt was aboard one of the many trading ships which called at Hobart from Batavia, or India. They brought rum, one necessary item. Given his situation, taking Elizabeth as his servant, or a servant of one of the officers, was not unrealistic.

Peter married Elizabeth in Calcutta on 2nd November 1813. They had a son William Doran Lette, who was born on 13th January 1815 and baptised at Fort William on 4th January 1816.

Peter Lette in 1814, in a resident's list of India, he was a Merchant. That then confirms other research that indicates he had an indigo business.

But, they also had a daughter Mary Ann. Some questions remain about Mary Ann. Was she just the daughter of Elizabeth Peck, and an unknown father, but then reared by Peter as his own? That was quite common, and given that Elizabeth was young, and vulnerable, anything was possible.

There are no births recorded in India for any other Letts or Pecks. There is however, a birth of a Mary Ann, no surname, not uncommon with transcriptions, who was born in 17 February 1809 and baptised in 17th December 1810, baptised Agra, Bengal. (V8p305)

Could that be the missing record for Mary Ann Peck?

In 1817, Mr and Mrs Lett, arrived on the 16th instant on the ship Hunter, Captain Hope from Bengal, with a valuable cargo of merchandise -

The missing headstone- Controversy has arisen about Peter Lemonde Lett's headstone, and why it was on the Gunn property.

Simple answer, Mr Ronald Gunn advised the Colonial Treasurer, in a note from Wynyard Table Cape 27th December, that he arrived there on the 21st and stated with Mr Lett for the Calder.

They found gold.

Peter was the only one of his father with such a middle name. Lemonde - In French it means "The World" quite an appropriate name for such a traveller.

His land

LETTE, Peter. Settler, Port Dalrymple

1819 Feb 13 Re grant of four hundred acres at Port Dalrymple (Reel 6006; 4/3499 p.313)

1823 Nov 18 Deposition re stolen timber (Fiche 3289; 4/7015.1A p.35)

Shipping to Australia

There is no doubt that Peter Lette was an officer on a ship that came to Hobart. The shipping between the two places was extensive, and at times, convicts were brought from India.

Given that the Porpoise returned in January 1808, it would be around that period that should be considered.

If the only Mary Ann recorded as a birth in India of February 1809, is connected, then timelines would suggest shipping in that year. A birth at sea, required the child to be registered at the next port.

That occurred with the third child. Perhaps Mary Ann was also born at sea on the way to India.

Nothing can be proven, other than they had a child Mary Ann.

Of interest there was a ship called the Mary Ann that left Bengal in 1809 for Australia.

As the partner of an officer, she may have travelled on a ship with him.

There are numerous ships that he could have travelled on, as the East India Ships travelled the world.

From Trove 1899

The Capes and Letts of Sydney and Relatives

Thrilling and interesting Memoir of a Brave Irish Boy

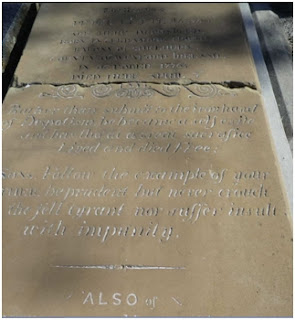

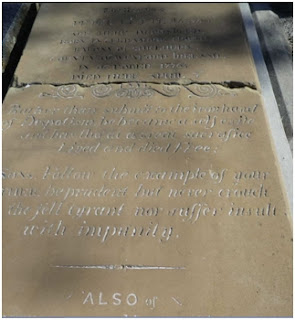

A Patriotic Epitaph.

The following interesting information has been placed at our disposal by a well-known resident of Monaro, N.S.Wales. It shows that the boy hero of the Battle of New Ross in the ’98 Rebellion afterwards went to sea, became a captain in the mercantile marine, achieved a competency in India and afterwards settled in Tasmania where his grave is to be seen to-day with a characteristic and stirring epitaph.

The son of Peter Lett afterwards removed to Monaro, New South Wales, where he still lives; while other descendants of the boy hero achieved Parliamentary distinction in Tasmania, and were connected with some of the best known and most widely respected families of Tasmania – including the Capes and Mr Charles Lett, the tall and handsome Civil servant who afterwards held a responsible position in London, and died there a few years ago.

It is a story that no son or daughter of Erin or their descendants in Australia can read without feelings of pride and admiration for the dauntless youth and livelong Irish patriot, Peter Lett.

What follows is from the pen of our correspondent:-

In the splendid peroration of his eloquent discourse at the “98 celebrations of Dr MacCarthy, with justifiable pride of race and country, relates the unparalleled act of heroism of the young boy Lett in the following words:

“Why, we have in the ’98 Insurrection and extraordinary and unprecedented instance of this instinct of leadership and its spontaneous development in the case of the thirteen year-old boy-leader Lett, who ran away from his mother in Wexford to join the insurgents, and who in a critical moment during the flight at Ross, snatched up the green flag, rallied two or three thousand pikemen, charged the garrison at their head, and drove the enemy back headlong on their supports. This sounds like romance. It is fact.”

It will be interesting to the patriotic doctor and to your readers generally to learn that, John M. Lett, Esq., J.P., now aged about 70 years, and a worthy and only surviving son of that young Irish hero, resides at Adaminaby, in the Monaro district, New South Wales. He too is a man of notable character, unbending, decided, upright, and honourable, according to his view of things. He has the natural qualities of a leader of men, and usually holds away in the transaction of matters of public interest in his district.

He is a man who made and lost fortunes ont he goldfield of California and Australia. He is also a man to whom a fellow-men has never appealed for help in vain when it was in his power to help him, or, as the diggers used to say in homely but expressive phrases, “He would give the shirt off his back if anyone asked him for it.”

On the other hand, he has always maintained his dignity, rights, and principles without flinching determination, and the martial proclivities of his race soon come to the surface if anyone tries to thwart or injure him. He is, in fact, a man of very strong, passionate feelings, either as a friend or an opponent, and will vehemently maintain without the slightest regard to personal interests or considerations, the side he think to be in the right and he might appropriately adopt his motto:

“Neme me impune inocasit”

It would be superfluous to say that he was intense sympathy with the ’98 Celebrations, and all will unanimously allow that his father’s name deserves an honoured place on any monument raised to commemorate the valour, unselfishness and patriotism of those who fought for Irish freedom.

In 1819 my father’s health broke down owing to the climate, and he decided to settle in Van Dieman’s Land to recruit his health. He brought the first large vessel which ever made the attempt to get up the river Tamar at Launceston, but could not enter the Heads entirely, loaded with a valuable East Indian cargo of produce. This ship had to be unloaded at George Town, and the cargo brought to Launceston in smaller vessels. I am the last survivor of this old family, the youngest having died about four years ago at Launceston. He represented Central Launceston in the Tasmanian Parliament for 27 years without a break, and most of the time he was Chairman of Committees. One of my sisters married one of the old Cape family of Sydney, and the younger one married a captain, Thomas Dutton, of the Royal Navy.

It was never known outside of our own family the active part which my father took in the rebellion of 1798. However, shortly before his death, he asked for all his sons to be brought to him and stand around his bed, and he addressed us in these words” “My sons, bear this in mind. I am leaving you a legacy which concerns you all, and it is this – If the time ever comes that Ireland wants your help, you must go to her assistance, no matter what the sacrifices you may have to make.”

My father died almost immediately afterwards. I was but six years old at the time, but everything is as fresh in my memory as thought it only happened yesterday.

One of the first acts of my father on getting to Tasmania was to gather and pension all he could find of the old Irish patriots who had been transported, many of whom lived long after my father died. But the greater number of those old Irish rebels had died, before his coming, under the brutal treatment in the convict gangs as meted out by the officers and soldiers placed over them.

It is now 64 years since my father died, and of course his coffin and its contents must now be only dust. His wishes were that his body was to be cremated, and the ashes gathered into a brass vase, upon which was to be inscribed his epitaph, and the vase deposited in a vault sufficiently large to contain the whole family. My father must have foreseen that a day would come when the heroic deeds and sacrifices made by those old Irish patriots would be remembered and .........people, And I thank God that I the last of his family, have lived to see it. No stronger Irish patriot ever lived than my father, and had his wishes been complied with, the vase containing his remains could have been brought over and interred with the other old patriots.

I have still his broadsword and rapier, and also a remarkable pair of old pistol-holsters, and a pair of larger, old-fashioned flint pistols, as used in those troublesome times; and now as I am verging to the end of my days, all that I would ask of the committee is to have a place on the monument about to be erected for my father’s epitaph.

My brothers all bore good old Irish names – Corlough, Doran, Mitchell, Dimond, Chambers, Elms. These were, I presume, surnames of old comrades who fought side by side with my father, Peter Lett.

A most remarkable incident occurred to me in New York in 1847. I was stopping in one of the larger hotels in that city when every hotel was crammed full of military officers expecting the declaration of war against Mexico. Amongst the officers stopping at this hotel was a white-headed fine soldierly looking old man, who hearing my names, asked for an introduction. He asked me where I hailed form, and I told him all I knew of my father’s antecedents. “Well young man,” he said, “Peter Lett and I fought side by side in many a hard fight in ’98, when little more than bys. I got over to America, but I never heard what had become of my old comrade, your father.” This man was then a General in the United States Army. I again met the same officer in 1850, and he (General O’Reilly) was then Governor of that State.

My father, although he fought and suffered for the rights of his Catholic fellow-countrymen, was not a member of the Catholic Church. He always told us he was the last of his race, and this was confirmed many years after. In 1844-5, five of my brothers were sent home to Ireland, and completed their education in Dublin, after which they all took up their professions.

Corlough was articled to Fletcher and Roe, solicitors, of Sackville Street , Mitchell went to a Dr Porter to study medicine, Peter Limond took up civil engineering; Chambers studied for the Church; and Doran, the “eldest” married an Irish lady and brought her back to Van Dieman’s Land. My brothers made every inquiry as to my father’s relations, but none were to be found.

The old home, Curragh Moor, had passed into other hands. There were some Letts in and around Dublin, Catholic families, but they were in no way connected with our old Wexford family; and when my brothers went home, the Marquis of Waterford owned my father’s old home, Curragh Moor.

I have a record of my father’s death as published in the Currency Lad in Sydney on the 27th April, 1833, but he must have died a fortnight before, as in those days it took a vessel about a fortnight to go from Launceston to Sydney.

There are many friends in Launceston who would gladly point out the family vault. There were several of my brother’s children settled in Tasmania – Ernest LEtt, Commissioner for Customs, Hobart, Corlough Lett, a mining manager; also my sister’s children, the Capes and Duttons.

My father composed his own epitaph some years before he died and it is inscribed on the slab of marble with covers the vault where the remains of my father and mother are.

****************************************************************

Peter Lette, mariner, of Curramore

House, Shelburn, County of Wexford, Ireland.

Born 1776, died April 3, 1833.

Rather than submit to the iron hand

of despotism, he became a self-exile, and has, though at great

sacrifice, lived and died free.

Sons, follow the example of your father;

be prudent, but never crouch to the

fell tyrant,

nor suffer insult with impunity.

The wife of Mr

Peter Lette died at Curramore on May 12, 1864, aged 72

years. Mr P.Lette became possessed of considerable property in

the north of Tasmania, including the fine estate of

"Curramore," nearly the whole of which was

bequeathed to Henry as the " bravest" of his sons, of

whom there were three. He had also two daughters, Mrs John

Cape and Mrs Captain Dutton, the latter of whom re sides at

Stewart Villa, Margaret-street.

Mr John Lette, one of the sons,

occupies a prominent position at the present time in New South Wales.

****************************************************************************

Peter Lett was involved with the Battle of New Ross, he was lucky to have escaped death.

Battle of New Ross (1798)

The Battle of New Ross took place in County Wexford in south-eastern Ireland, during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. It was fought between the Irish Republican insurgents called the United Irishmen and British Crown forces composed of regular soldiers, militia and yeomanry. The attack on the town of New Ross on the River Barrow, was an attempt by the recently victorious rebels to break out of county Wexford across the river Barrow and to spread the rebellion into county Kilkenny and the outlying province of Munster.

On 4 June 1798, the rebels advanced from their camp on Carrigbyrne Hill to Corbet Hill, just outside New Ross town. The battle, the bloodiest of the 1798 rebellion, began at dawnon 5 June 1798 when the Crown garrison was attacked by a force of almost 10,000 rebels, massed in three columns outside the town. The attack had been expected since the fall of Wexford town to the rebels on 30 May and the

British garrison of 2,000 had prepared defences both outside and inside the town. Trenches were dug and manned by skirmishers on the approaches to the town while cannon were stationed facing all the rapidly falling approaches and narrow streets of the town to counter the expected mass charges by the rebels, who were mainly armed with pikes.

Bagenal Harvey, the United Irish Leader recently released from captivity following the rebel seizure of Wexford town, attempted to negotiate surrender of New Ross but the rebel emissary Matt Furlong was shot down by Crown outposts while bearing flag of truce. His death provoked a furious charge by an advance guard of 500 insurgents led by John Kelly (of ballad fame) who had instructions to seize the Three Bullet Gate and wait for reinforcements before pushing into the town. To aid their attack, the rebels first drove a herd of cattle through the gate.

Another rebel column attacked the Priory Gate but the third pulled back from the Market Gate intimidated by the strong defences. Seizing the opportunity the garrison sent a force of cavalry out the Market Gate to attack and scatter the remaining two hostile columns from the flanks. However the rebel rump had not yet deployed and upon spotting the British manoeuvre, rallied the front ranks who stood and broke the cavalry charge with massed pikes.

The encouraged rebel army then swept past the Crown outposts and seized the Three Bullet Gate causing the garrison and populace to flee in panic. Without pausing for reinforcement, the rebels broke into the town attacking simultaneously down the steeply sloping streets but met with strong resistance from well-prepared second lines of defence of the well-armed soldiers. Despite horrific casualties the rebels managed to seize two-thirds of the town by using the cover of smoke from burning buildings and forced the near withdrawal of all Crown forces from the town. However, the rebels' limited supplies of gunpowder and ammunition forced them to rely on the pike and blunted their offensive. The military managed to hold on and following the arrival of reinforcements, launched a counterattack before noon which finally drove the exhausted rebels from the town.

No effort to pursue the withdrawing rebels was made but when the town had been secured, a massacre of prisoners, trapped rebels and civilians of both sympathies alike began which continued for days. Some hundreds were burned alive when rebel casualty stations were torched by victorious troops and more rebels are believed to have been killed in the aftermath of the battle than during the actual fighting. Reports of such atrocities brought by escaping rebels are believed to have influenced the retaliatory murder of over 100 loyalists in the flames of Scullabogue Barn.

Casualties in the Battle of New Ross are estimated at 2,800 to 3,000 Rebels and 200 Garrison dead. An Augustinian Friar at New Ross on 5 June 1798, the day of the Battle, entered in the Augustinian Church Mass Book the following in Latin: "Hodie hostis rebellis repulsa est ab obsidione oppidi cum magna caede, puta 3000", ("today, the rebel enemy was driven back from the assault of the town with great slaughter [carnage], estimated at 3000".)

A loyalist eye-witness account stated; "The remaining part of the evening (of 5 June 1798) was spent in searching for and shooting the insurgents, whose loss in killed was estimated at two thousand, eight hundred and six men."[5] This second figure is probably the most accurate of all figures given – it indicates that an attempt to make an accurate count had been made.

Most of the dead Rebels were thrown in the River Barrow or buried in a mass grave outside the town walls, a few days after the Battle.

The remaining rebel army reorganised and formed a camp at Sliabh Coillte some five miles (8 km) to the east but never attempted to attack the town again. They later attacked General John Moore's invading column but were defeated at the battle of Foulksmills on 20 June 1798.

John Maximus Lett and his sons Donald and Frank had their gold mine out at “New Clune Hill”. John was also a Kiandra Magistrate and a storekeeper. The Chinese residents of Kiandra had been given the right to purchase property in the town centre and on 15th November, 1882, Catherine and Thomas Yan purchased John Lett’s store, including a number of other weatherboard buildings.

Kiandra - Gold Fields to Ski Fields By Norman W. Clarke

John’s daughter was Elizabeth Mary Maude Lette, born 1873 in Cooma, NSW.

She married in 1890, George Peter Harrisson in Deniliquin. They had a daughter Rosa Kooringa Harrison, born in Burra South Australia, who married in 1936, Jos. Watson in Victoria.

She married in 1913, Henric Thomas Jillett, born 1848 – 1917, and they had a daughter Nancy Mary Jillett. Nancy died as an infant in 1914. Henric died in 1917.

She then married in 1919, Edward James Alfred Linnell 1885 – 1949. She divorced him in 1921.

The marriage of Elizabeth to Henric Jillett, was the second “merging” of the families of Peter Lett.

His daughter, Honoria married into the family of Henric’s niece’s husband, through the Kingdom and Mudge lineage.

1798

Memorial, Waverley Cemetery

The 1798 Memorial, made of marble, bronze and mosaic, in Waverley Cemetery, Sydney,

is the finest 1798 Memorial in the world. It was raised over the grave of a

famous Irish character, the Wicklow Chief, who died in Sydney, long after the

events of 1798.

The Wicklow Chief

Michael Dwyer, the Wicklow Chief, is a well-known historical figure in Ireland. Irish people know that he took part in the 1798 Rising in Wexford, and when the Rising had been quelled, he continued the fight in his native Wicklow hills. Irish people generally do not know that he is buried in Sydney.

On 14 December 1803 Dwyer surrendered on condition that he be sent to America. He was sent to Australia. He arrived in Sydney on 15 February 1806 with his wife, Mary, on the convict ship, Telicherry. He was classed as a state prisoner, not a convict. Governor King had to treat him as a free settler. He gave him a grant of 100 acres (40.4 hectares) along the Cabramatta Creek outside of Sydney.

He died in 1825 and was buried in the Devonshire Street Cemetery in Sydney. His wife, Mary, died in 1860 and was buried with Michael.

Centenary of the 1798 Rising

With the approach of the centenary of 1798, the Sydney Irish decided to find a conspicuous resting place for the Wicklow Chief. They paid £50 for a plot of ground at Waverley Cemetery. They could have obtained one for free in Rookwood Cemetery, but it would not have been in such a marvellous position overlooking the sea. Under the leadership of Dr Charles William MacCarthy, they engaged John Hennessy of Sheerin & Hennessy architects to draw up a plan for a memorial to place over his tomb.

Removal to Waverley

On Holy Thursday, 19 May 1898, the vault at Devonshire Street Cemetery was opened to remove the bodies of Michael and Mary Dwyer. The two coffins were placed in a large cedar casket and brought to St Mary's Cathedral on Saturday night, 21 May. At 2 pm on Easter Sunday the casket was taken to Waverley Cemetery in the largest funeral Sydney had seen up to that time. The casket was placed in a vault and Dr MacCarthy laid the foundation stone of the monument to be built over it. The completed monument was opened on Easter Sunday 1900.

The monument

A rectangular platform, 9 metres wide and 7 metres deep, made of white Carrara marble, was raised over the vault containing the bodies of Michael and Mary Dwyer. A white marble cross, with intricate Celtic intertwining, was placed in the rear wall, rising nine metres into the air from the ground. Carved on the base of the cross are the words

In loving memory of all who dared and suffered in Ireland in 1798.

On the sub-base of the cross are the words

Pray for the Souls of

Michael Dwyer the "Wicklow Chief"

and Mary his wife whose remains are interred

in this vault. Requiescant in Pace.

The Latin phrase means 'May they rest in peace'.

A wall 1.83 metres high runs along the back of the platform. The wall is stepped down at the sides of the platform so as to be only 0.8 metres high at the front. Two bronze wolfhounds couchant sit on the front terminals at each side. Three bronze plaques, designed and made by Dr MacCarthy, as was all the bronze work, are placed in the rear wall at each side of the marble cross. The ones at the left represent Wolfe Tone, the capture of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, and Lord Edward Fitzgerald. The ones at the right are Michael Dwyer, the battle of Oulart Hill and Robert Emmet. High on the side of the cross on the left is a plaque with a bas relief of Henry Joy McCracken and on the right, a bas relief of Father John Murphy.

The platform is on two levels, both 7.3 metres in width. The first level, six steps up from the ground is 4 metres deep – the second level, a further two steps up, is two metres deep. Both are paved with gold mosaic, which has designs in green and blue and brown mosaic depicted in it. In the centre is a mosaic blue-green harp, with a female figure forming one side, which was a common custom in the eighteenth century. On each side of the harp is depicted a thatched cottage and a round tower. Artisans from Anthony Hordern's in Sydney did the mosaic work.

The bronze fence

A bronze fence with gateway was positioned across the front of the monument in 1927 to deter vandals. It was designed by John F Hennessy before he died in 1924. The gate in the centre has an ornamental shield. At each side are panels with the Brian Boru harp depicted on a rising sun background. There are intertwined snakes under the harps.

The side facing the sea has an inscription in the Irish language, which may be translated:

People of Ireland treasure the memory of the deeds of your ancestors. The warriors die but the true cause lasts for ever.

The side facing west has an inscription in Irish, which translates 'May God free Ireland'. It also has an inscription running the full width of the wall in Ogham, which was a script formed by straight short lines across a base line. It was used in early Christian Ireland. Translated, the inscription reads:

The bright days of ancient Ireland will dawn once more.

Recording the names

On the rear wall are 76 names of men and women, priests and ministers, who took part in the 1798 Rising. Below them are the names, added in 1947, of those who were executed after the 1916 Rising. In 1994 the Irish National Association, to whose care the Monument is entrusted, placed a plaque behind the monument to commemorate the ten Irish Republican hunger-strikers, who died in the Maze prison, Belfast, Northern Ireland, in 1981.

The Irish National Association holds a ceremony at the Monument every Easter Sunday afternoon.

In Ireland

On 1 November, 1898, Father Kavanagh laid the foundation stone of the Wexford 1798 monument. Kavanagh said that the monument would be proof to future generations that we were imbued with the spirit of the men of ‘98…The men, whose memory we honour today, died for a persecuted creed as well as an oppressed county…Their blood was not poured forth in vain. It made the earth which drank it ever sacred to freedom; with their expiring breath they kindled the embers of a fire which burns still. Kavanagh identified the modern political struggle for self-determination with the monument yet to be erected.

The choice of the Bull Ring for the monument was symbolic. It was there in 1641 that Cromwell, having seized Wexford, killed men and women of the town. A fragment of the former Market Cross was incorporated in the foundations, thus linking the monument to the early Catholic life of the town.

It had also been the site of a 1797 munitions factory where blacksmiths worked continuously to forge pikes and repair weapons. The foundation stone came from Three Rocks, site of one of the battles of the Rebellion.

The laying of the foundation stone became a political demonstration. The streets of Wexford were decorated with flags and evergreens, and the parade included horsemen and marching bands. The foundation stone itself was guarded by men dressed as rebel pike men of 1798. Constitutional nationalism was powerfully represented by the presence of four Irish MPs: John and William Redmond, Peter Ffrench and Sir Thomas Grattan Esmond. The main organisers in Wexford were Simon McGuire of the newspaper, The Free Press, who publicised the project.

Oliver Sheppard and his sculptor friend and exact contemporary, John Hughes, were invited to compete for the commission. It went to Hughes, then based in Dublin, who agreed to model the figure, but refused to accept the committee’s time limit, thus forfeiting the commission. When Sheppard returned to Ireland to his new teaching post in July 1902, he was invited to meet the Wexford ‘98 Committee. They told him on 10 September ‘our idea of the monument is a figure…of an insurgent peasant (about seven feet high) with pike in hand and in a defiant attitude’. In defining their ideas, they had theadvice of a local priest.

By October 1902 Sheppard was modelling a small clay study of the figure. He signed a contract which stated that if any dispute arose it was to be referred for arbitration by an architect or engineer appointed by John Redmond or Dr Walsh, Catholic Archbishop of Dublin. It is evident that this entire operation was in the orbit of the parliamentary nationalist and Catholic authorities.

In 1903 Sheppard worked on a quarter-sized model, using a pike-head sent to him by the Wexford committee. Over the summer, he completed a full-scale figure in clay which was cast into plaster. Finally, in August, this plaster cast was sent to Paris to be cast into bronze by E. Gruet. In February 1904 the completed bronze was sent to Ireland. A limestone pedestal was supplied by D. Carroll of Tullamore to Sheppard’s specification. The date ‘1798’ alone was cut in the pedestal, despite the misgivings of some of the committee who wanted a further text in case ‘people would lose sight of the object for which the monument was erected’.

The bronze figure was exhibited at the Royal Hibernian Academy, Abbey Street, Dublin, in March 1904, after which it was stored in Wexford Town Hall. In March 1905 the limestone pedestal was put in position in the Bull Ring and the figure set upon it.

Unveiling

The unveiling on Sunday, 6 August, 1905, was the culmination of the campaign begun in 1898. About 30,000 people attended with excursion trains from Dublin and a group from Liverpool too. The night before, bonfires heralded the event. The Bull Ring was elaborately decorated with festoons and arches. A large outline of the number ‘98’ and pikes crossing was spelled out in gas jets at the gas works. Similar gas-litre presentations of a wolfhound and a round tower were displayed at the Pierce engineering works; on the lamp posts were images of pike men. The day of the unveiling began with an elaborate procession with marching bands from all over the county. It was a spectacular political rally.

https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/1798-1898-the-political-implications-of-sheppards-monument/

Just in case it will assist another researcher, the list of ships that docked in Australia follows.

No comments:

Post a Comment